Running through treacle. It’s the best way to describe March. Everything was an effort. Getting the most basic message across took time. For the products and programs team, it felt like any effort was wasted. And they almost gave up.

In March, the Wadhwani Institute for Artificial Intelligence was set to run its pilot program on cotton pest management. The solution looks pretty simple from the outside. Farmers set up traps, monitor, install an app, take a picture, AI gives them a suggestion, they implement the suggestion, they manage to ward off pest attacks. It’s almost like reciting the alphabet.

But in reality, the alphabet is difficult, especially when you both speak different languages. The English alphabet has 26 letters. Kannada, a language spoken in the South of India, has around 50. Not just language, how do you teach a 35-year-old farmer how to use an app when all they don’t even have a smartphone. Even if somehow you could get through, find a way to process their images, how do you determine that the farmers actually follow your advice?

These are challenges even when you aren’t asked to shelter in place. The solution before the pandemic? The team would split into small groups and go to different villages in districts, onboard farmers, set up processes and then return. But how do you handle it in a lockdown? Even with masks, the Coronavirus can infect people. Apart from the health risk is the logistical issue, how does one get around during a lockdown? This part of the job couldn’t be done with social distancing.

But when things get weird, the weird turn pro.

There is always an answer

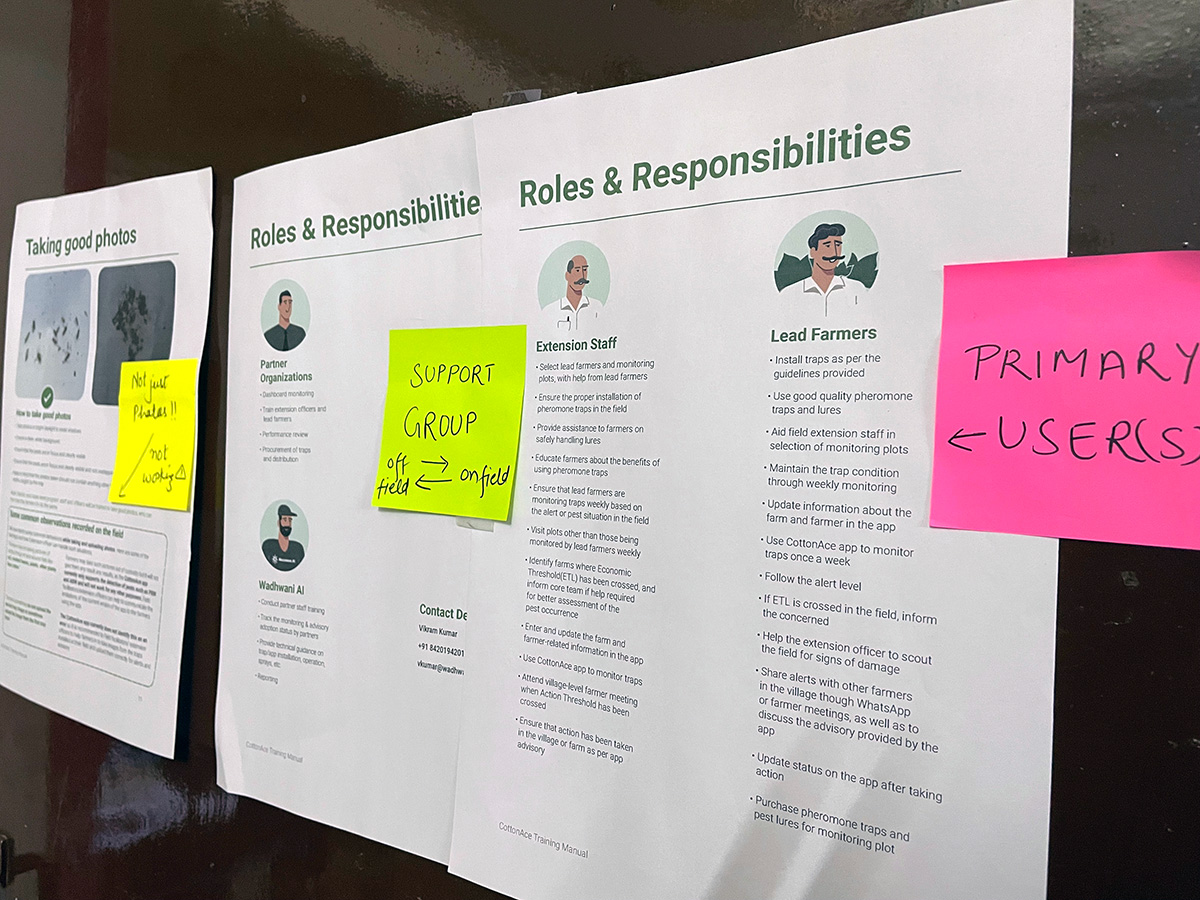

There is a simple solution. Hire. But hiring comes with challenges. How do you describe a program and its nuances at its pilot stage to an entirely new set of people? Even though the basics are easy, the key here is not just explaining the solution to a farmer but also to convince her that the phone is giving her the right answer. Farming in India, to a large extent, is an occupation that is inherited and so are the methods. It is difficult to convince farmers that the times have changed and their thinking needs to evolve. New problems need new solutions. And these solutions are hidden in technology.

“We have to be careful not to overcommit,” says Rajesh Jain, senior director, programs, Wadhwani Institute for Artificial Intelligence. The solution can’t be the pest equivalent to the one ring.

The team had to reimagine the entire pilot. So they started small. Let’s hire a manager. But a manager that is in the district. This is a tricky task. Finding experts who not only can speak the language but are geographically close and understand pests and cotton is difficult. Fortunately, in a team’s earlier visit in February, they had managed to make connections with officers in the agriculture department. This proved to be a valuable link. The officers helped the team find the right manager. Now the plan was to get this manager to go to individual villages, talk to sarpanch (elected leader of a village), get consent and find out how many farmers could be interested. While the sarpanch gathers the farmers and gauges interest levels, the manager starts to hire a team.

The pitch by the manager: The job is on a short term contract and is going to require a lot of travel during a pandemic. But you help cotton farmers and teach them to install the traps and use the app properly on their phone.

And it worked. We managed to hire three extension workers. The sarpanch and lead farmers of different villages helped with the numbers and contacts of farmers. Almost 120 farmers volunteered to try the solution. The extension workers were assigned to the farmers. The process was now split into two parts. One would be at the village level.

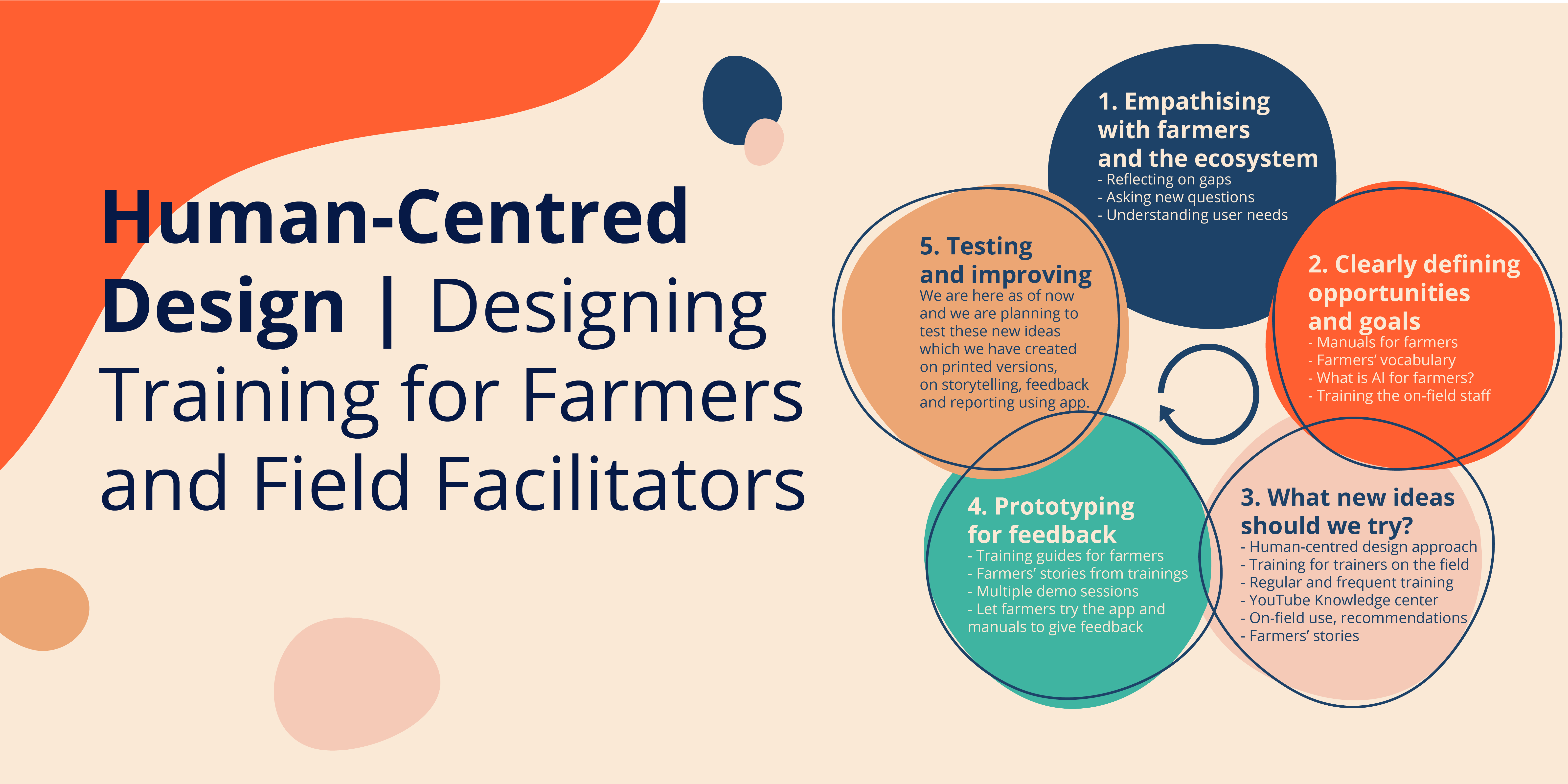

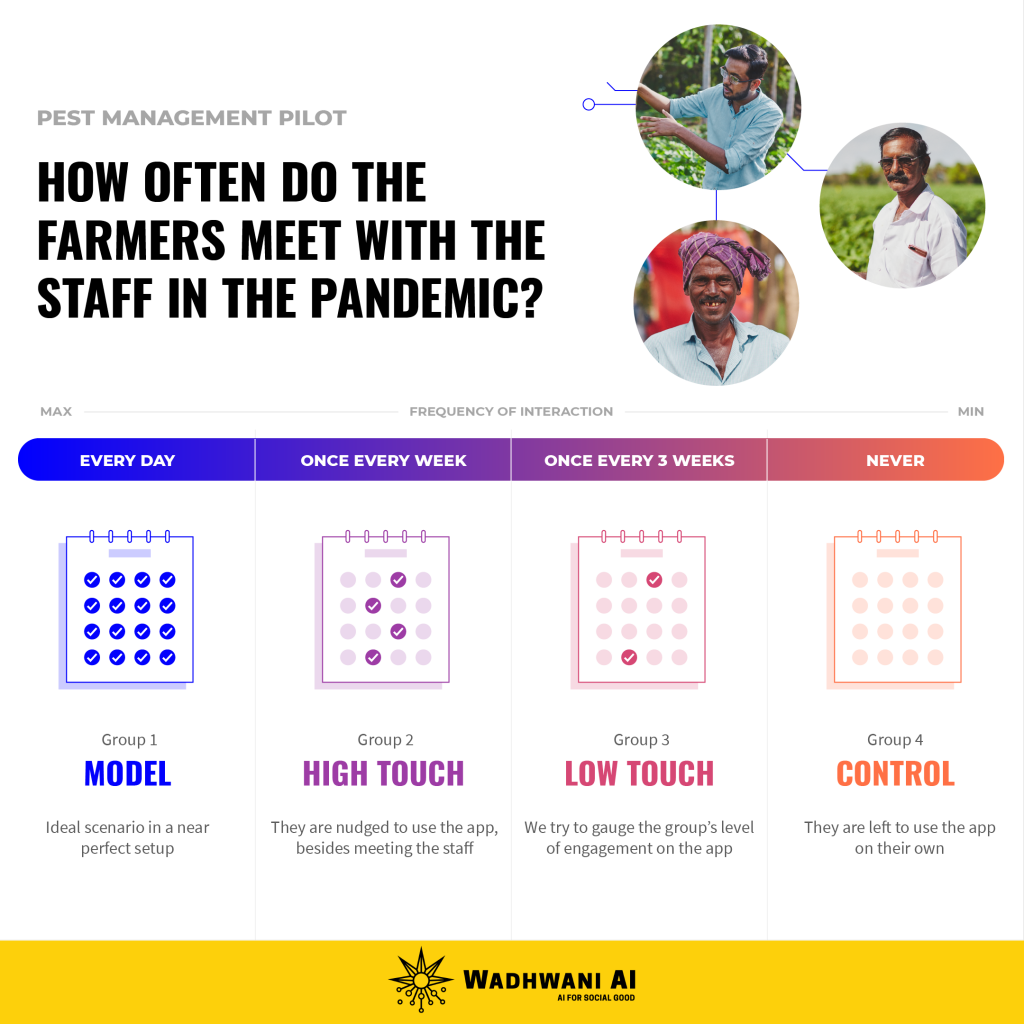

This is where the extension workers and the manager would be the face of the institute. They would be responsible for whipping up excitement. The team would work quietly in the background course-correcting when needed. For the sake of the pilot, the team split the farmers into four groups.

Now it gets tricky. Everything the team made was in Mumbai. Hubli is a small district in Karnataka about 570km from the Institute’s headquarters. The languages spoken in both states are different. Even the script is different. To add to this, everything made by the team was in English.

“Google translate was our answer. English was converted to Kannada, our onboarding posters and charts were translated. Our advice on the phone was translated too,” says Rajesh.

It is a neat workaround until you realise that language throws up funny quirks. “Our in-app advice to a farmer involved us giving him an option to choose between three types of pesticide,” says Rajesh. Something broke between the translation and interpretation and the farmer interpreted the or as and tried to find all three pesticides. “He couldn’t find all three so he called us and told us that our advice didn’t work,” adds Rajesh.

This was important learning. It meant there was more training needed.

The team’s idea was to create a video.

A video would be self-explanatory. But the language was a problem once again. “The managers came up with their own solution here,” says Rajesh. The manager watched the video, understood the process and went to the farms.

Here he repeated the processes in the video but he spoke in Kannada while explaining the steps to the farmers. This entire process was recorded and posted to a WhatsApp group. The video was watched by most farmers in the group.

Two-factor authentication

The WhatsApp group plays an important role in the pilot. “Not only was it a one-point contact for our pilot, but we could also educate the farmers about masks and social distancing,” says Rajesh. In the first few months of the virus hitting India, smaller districts were aware of the virus but not of the seriousness primarily because the infection hadn’t left the cities. This WhatsApp group convinces farmers that if they follow the advice, it may help their crop. It is also a place for exchanging ideas, learning new techniques and a place for social interaction.

Now with the technology in the hands of the farmers, it is important to determine if the farmers actually use it correctly and regularly. Just asking the farmers isn’t enough. So the team put in place a two-factor authentication system. The extension workers hired by the institute entered an informal partnership with the local pesticide seller. The agreement? You tell us when one of our farmers buys a particular product. Now, each time one of the farmers that were part of the pilot bought a pesticide, the institute would know. It created a feedback loop. But there is still a gap between purchase and use.

“The extension worker would take a picture or video of the farmer spraying the pesticide,” says Rajesh. This would complete the cycle. Now, the institute would know that not only was the information reaching the farmer, he was also implementing the advice.

Setting up this entire pilot from scratch took 27 days. The team is quietly very happy with their effort. And there have been plenty of learnings too.

“If I could go back in time, I would fix our communication. Every time we slowed down it was because we couldn’t get our message across. It was usually language issues. You can only go so far with videos and Google,” says Rajesh.

So what would you do differently? Hire someone who understood a little more English. It is a minor quibble though, Rajesh admits. It is a complex set of instructions have to be delivered remotely, even if the manager was fluent in English.

Rajesh believes that this is not just a successful pilot for Wadhwani Institute for Artificial Intelligence but also for anyone who wants to run an agri-tech program in the developing world. “Look, the virus isn’t going anywhere soon. We will have to learn to conduct our programs remotely. And this is going to be the blueprint going forward,” says Rajesh.

His advice to anyone attempting something similar? “The time is ripe to use technology to solve old problems, you just need to have the conviction,” Rajesh adds.